Web-Exclusive Interview: SSG Mark Lalli Talks About Surviving a Helicopter Crash

"The aircraft started to spin. Not really thinking it was anything unusual, I remember calling the pilot saying, 'Hey sir, are we going to stop this?' When he responded with, 'I can't,' I knew this wasn't going to end well."

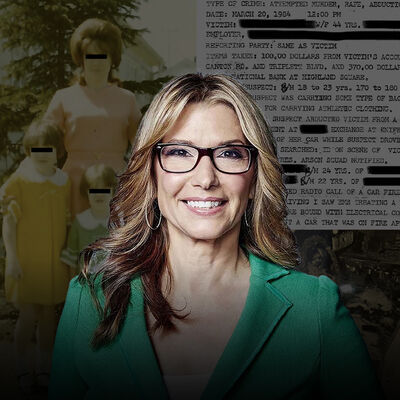

In this web-exclusive interview, the Host of Warriors In Their Own Words, Ken Harbaugh, sat down with Staff Sergeant Mark Lalli to talk about his service in the Army. Lalli served in Iraq as a Blackhawk Helicopter crew chief and survived a helicopter crash that killed six of the eleven passengers on board, but he sustained life-changing injuries.

For more interviews like this, check out our podcast, Warriors In Their Own Words. New interviews with veterans from every American conflict since World War II are released each week.

Ken Harbaugh:

Could you just start by sharing with us your name, your rank, when you got out, and your MOS, what you did in the Army? And what years were you in the service?

SSG Mark Lalli:

Sure. I am retired Staff Sergeant Mark Lalli. I was a Blackhawk crew chief and flight instructor with the US Army. I was a reservist from 2002 to 2004, and then I was active duty from 2004 to retirement in 2010.

Ken Harbaugh:

So 2002. I'm going to assume that 9/11 had something to do with you signing up. Can you talk about where you were on that day and what was going through your mind?

SSG Mark Lalli:

I was a sophomore, and I was a 15-year-old sophomore in high school. 9/11, happened about a month and a half before my 16th birthday. Watching the pictures on TV during no less American history class really made me think back. My grandfathers both enlisted in the Army after Pearl Harbor. One grandfather signed up on December 8th and the other one a little bit later, and their military or Army service always was an interest of mine of following my grandfathers. One of my grandfathers was in the Pacific, one was in the European theater. The one in the Pacific did seven invasions throughout the islands doing artillery for the Army, and tracing his jumps throughout island to island was just always impressive and always something that really inspired me. It really encouraged me to serve something better than me, and 9/11 was my Pearl Harbor moment. It was my time saying, well, you know what, let's go for it. We'll apply for college because what we're supposed to do, but I was that joined the military. So at 17, I signed up in the Army reserves to... I did my bootcamp between the summer vacation between junior and senior year of high school. How I spent my summer vacation essay was pretty funny that following Fall.

I applied for the US Army or the US Military Academy at West Point when like 97% of other applicants got a rejection letter I said, well, let's go active duty. I'm already halfway there, so let's go the way. I signed up to become a Blackhawk helicopter mechanic hoping that I could become a crew chief and not only maintain the aircraft, but also fly the missions and play with this really big toy. It looked like fun.

After finishing high school, I went to my job training at Fort Eustis, Virginia where I finished at the top of my class, and then upon graduation I was assigned to a unit at Fort Hood, Texas where our primary mission was to fly air assaults. We would pick up an aircraft full of ground forces whether it be infantry, military police, artillery engineers, and drop them off behind enemy lines to do what they did during the day. And then, we come back and pick them up about 24 or 36 hours later and fly them home, and then do the same thing over again the next day. In combat, our days are pretty carbon-copied. You wake up, you eat your breakfast, you go to the flight line, you flied aircraft, you fix what you need to and you go fly a mission, come home, pause flight, fix what you need to, and go to have some chow and go to sleep, repeat the next day. It was great. I miss combat because of the purpose we had there and the necessity we had there.

When I was in theater in Iraq, IEDs really became the new MO of the insurgency, and in order to keep our troops safe and our brothers and sisters safe we would fly them from base-to-base instead of driving them because it was safer to be up in the air. It's be a harder target to hit. So, that was our big secondary mission there a lot. So it was just very versatile, very utilitarian. You could do like a pocket knife, a Swiss Army knife.

Ken Harbaugh:

Yeah. Are there sensory things about it that come back to you? I always remember the smell of the cockpit. Do you think about the vibration? That's an airplane with enormous power. Do you think about the low altitude nap-of-the-earth flying? Is there anything that you miss most of all?

SSG Mark Lalli:

Hm, yeah. Oh, I miss all of that. I don't miss 90% of the day-to-day stuff on the ground, but I miss flying. I loved nothing better to be hanging like a dog in a car hanging my head out the window, looking around. The smells, seeing the earth fly under you, just see it roll, see it and watch the rivers and the lakes and stuff, and just the sound of the aircraft, the vibration, it kind of rocked you to sleep a little bit. Well, not really, but every time the aircraft would turn the jolts stuff that you would feel, yeah the vibration, everything sensory was just incredible.

Ken Harbaugh:

So you started out as a mechanic. What's the training like, and how confident were you that you could make the leap to crew chief because you wanted to be in the air, you wanted to be flying, right?

SSG Mark Lalli:

Yes sir. Yes, sir. The schoolwork to be trained as a mechanic was... Yeah, it was difficult enough. You really had to learn how to follow the book and follow the proper procedures to really make sure you achieve things to the standard. That was tough for me, but just being consistent, having your nose to the grindstone to really get the work done that you needed to at the proper standard to get to where it could be, yeah. It was a life or death situation, and that's something that I kind of miss nowadays is that I miss the... The civilian sector doesn't really have that, it must get done and it must get done properly or otherwise people can get hurt that we had back then. That was really essentially to do things right and I miss that. I miss being in the air. I miss being with my brothers and sisters and the camaraderie we had as crews, and just that tight-knit, that tight, close community.

Ken Harbaugh:

And then you decided at some point that you were going to make the leap, talk to me about your thinking going from being a ground mech. I assume you were mostly on the ground, to wanting to be in the aircraft in harm's way, completing the mission upfront.

SSG Mark Lalli:

So you have to start off in a maintenance company as a ground guy, as aircraft, but we were the unscheduled maintenance platoon. As aircraft would break, we'd fix them to get them up back on the flight line.

I had always wanted to be in the air from the very moment I started with it. I accepted the fact that I had to start off on the ground, and I did what I could to get there faster.

And actually, when Hurricane Katrina hit New Orleans, our company was in Texas. We were the closest aviation asset within the regular Army to New Orleans.

So our battalion mobilized and helped to fly support for food, water, moving evacuees throughout the city. This was about two months before we were set to deploy to Iraq when our battalion leadership decided that we're pretty short-staffed in the flight companies. That opened up a lot of opportunities for those of us in the ground companies to progress and become crew chiefs, be put on flight status for the deployment coming up. And with my records, with my work ethic, I was able to get one of those slots to be a crew chief, and I was able to progress to being on a flight crew before we went to Iraq.

Ken Harbaugh:

What does a crew chief do?

SSG Mark Lalli:

Crew chiefs, they do everything there. We're the eyes and the ears for the pilots in the back of the aircraft. They wiggle sticks and they take care of the radios, and all that fun stuff. We take care of everything else. We maintain the aircraft, we maintain airspace surveillance for the pilots behind them. They are in our rearview mirrors on a Blackhawk, so we are the rearview mirrors for that aircraft. You hang your hat out the window and make sure that you're not going to hit anything, and make sure that nothing's falling off, nothing is out of the ordinary. You make sure that the systems are all working properly before and after you take off. If you have passengers, make sure they're all safe and secure. If you're a carrier of cargo, whether it be internal in the cabin or whether it be external and hanging down from the bottom of the aircraft as a sling-load, making sure everything is safe and stable and secure and not going to fall out.

Ken Harbaugh:

You talk about making sure all those systems are working. Obviously, the most important system on that plane is the crew itself. Can you talk about the feeling after the first few months on deployment when you're just in sync with that crew and you're all thinking together and you know what the pilots are thinking before they even say it and vice versa? For the civilians, especially who are listening, share what that feels like to be part of a crew that feels like an extension of your own body.

SSG Mark Lalli:

In Iraq, our crews changed often, rarely were we with the same pilots, and when we flew in air combat we had two crew chiefs and two pilots per aircraft. Rarely were we with the same pilots and same other crew members or crew chief throughout the deployment. We rotated daily your primary mission for whoever needed how many hours, whoever needed to fly certain missions. So it was routine that we would rotate stuff, but because of our trainings, because of our proficiency with each other and with the aircraft with the mission, it was seamless. No matter who was in the front seat, and no matter who was with you in the back, we all worked together. We all knew what to do. We all knew each other's kind of thought process, how to anticipate stuff, how to deal with the hiccups as they came along.

Ken Harbaugh:

What was a typical day in Iraq like from the moment you get the alert or however they mobilized you guys to coming back and racking out?

SSG Mark Lalli:

One day you wake up, you go to the chow hall, and you grab your breakfast, or dinner, or lunch, or whatever per your schedule. You go to the flight line, you pre-flight the aircraft, you do whatever maintenance needs to be done per before the flight if you're flying. If you're on the ground that day, you find out what needs to be fixed to fly, so the aircraft could fly the mission the next day or you're ready for that mission that night. And if you are flying, pre-flight you get the crew brief, you get the mission brief. You find out where you're going, what you're going to do, what your mission profile is for that day, and you strap it on and you go fly your mission. You know where you're going to get gas. We're going to pick up other passengers, drop passengers off, drop off supplies, things like that. And then, usually you eat lunch in the air, come home, and post-flight make sure there's no damage, nothing. And if there's damage, if there's anything that can be replaced or be repaired, so that way we can go again either of that night or the next day, and be ready for the next crew to take over, take the keys when they come on shift. And then, you go back to the chow hall, get some food, go rack out for the night. That's carbon copy, repeat the next day.

Ken Harbaugh:

Did that Groundhog Day aspect of deployments in Iraq become reassuring after a while? There's a difference between monotony and predictability and I know some people who just love the predictability of that routine.

SSG Mark Lalli:

It was very monotonous and it was very predictable, but it had a purpose and it had a reason behind it. I am a creature of routine. My wife, my kids will say that once it's this time, dad is going to be doing this, it's one o'clock, okay, dad's going to be eating this lunch, he's going to be doing this. It has helped, especially with my... I have a severe traumatic brain injury and the routine of predictability and that structure has helped me stay on task where I don't forget things as much as I used to. I know how to prepare for what's going to come up next, and that routine, that predictability, and combat really helped us stick to a page and stick to a plan, and really have proper plan equals proper performance. So that good plan and that good predictability had us performing at a high level where we could react to things, we could incorporate things, we could be productive.

Ken Harbaugh:

Were there moments that stood out when that routine was interrupted? Share with us times you were really surprised by what was happening around you, either in the air or on base.

SSG Mark Lalli:

Thankfully, nothing in Iraq really happened where the routine was disrupted in flight. Every now and then we had something we had to adjust or redirect, but with our training, with our comfort with each other on the cruise, it was easy to really go with the flow. On the ground if an aircraft broke or was unserviceable for a mission, we were able to change aircrafts easily, and quickly, and properly to get us up off the ground to continue the mission and to air forward. So that really wasn't, that's nothing really out of the ordinary with that.

Ken Harbaugh:

Could you tell in a noisy, vibrating Black Hawk if people on the ground were taking potshots at you?

SSG Mark Lalli:

Occasionally. We came under fire twice that I know of. One time, it was during the day. We landed and on the post-flight, I found a hole in the bottom of the aircraft. I'm like, huh, guess I got shot at today, huh, okay then. At the time, we were flying at night and there were traces and fires coming up at us from the ground, so you could see the tracers. Thankfully, they shooted away from us, so they were shooting at the noise, but it was really inconsequential and insignificant, and just a part of daily life.

Ken Harbaugh:

You say that so nonchalantly, but tracer fire is both beautiful and terrifying. Most people in the States, even avid gun owners and target shooters aren't loading tracers. That is really quite a sight, isn't it?

SSG Mark Lalli::

Uh-huh, yeah. Yeah it is. As long as it is going in the opposite direction, it's pretty cool to see it. Like, ah, that's pretty neat. Watching the stream like, oh, that's cool, but knowing that there's four other rounds between each of those shows. At first you're like, oh it's best we bring some firepower there, but it's a lot like watching the 4th of July fireworks happening. But, a little more unexpected than the fireworks, but still it's interesting to see.

Ken Harbaugh:

Were your Black Hawks armed at all?

SSG Mark Lalli:

In Iraq, we carried two M2 40 cal machine guns. It was a 7.62 mm belt fed, gas operated machine gun platform.

Ken Harbaugh:

And were you on those guns as a crew chief? What was your role with those?

SSG Mark Lalli:

Yes, sir. As crew chiefs, we are their door gunners.

Every Vietnam movie has that picture or image of the guy hanging out the side of the Huey with a machine gun, that was us.

But in the Black Hawks it was a different weapons system. But, that was us in-country in combat, and in civilian places obviously I'm flying around unarmed. It's still the same setup where we're sitting in the seat behind the pilots and we're hanging out the windows like dogs.

Ken Harbaugh:

In Iraq, I imagine it was generally pretty warm. Were you always flying with the doors off or open?

SSG Mark Lalli:

The crew chief doors, the gunner doors, we were always open because we always had to be outside the aircraft doors. They always had the weapons system outside. The cabin doors in the back, we were nine times out of 10 doors closed. We had a couple incidents where passengers in the back would lose a sensitive item or a piece of paper, and so we got told we need to keep the doors closed which made it hot and uncomfortable. But, Iraq is hot and uncomfortable, so it's par for the course. Right.

Ken Harbaugh:

Yeah. I know complaining is part of aircrew culture and if you're not complaining, you really need to be worried. But what were some of the funnier complaints about being a 60 crew chief? Was there anything particularly eye-rolling?

SSG Mark Lalli:

You make up your own humor as you go along. A lot of gal's humor, a lot of practical jokes with the boss and with the other crew members, but a lot of times with passengers. In Iraq, we had vests that would have antifreeze type fluid in them to keep us cool. Crew chiefs rarely wore them because we were always in out of the aircraft so often during the day, but the pilots would wear them sitting up front. Oftentimes I would mess with those pilots, especially one pilot in particular where I would unclip the tube for her vest. So all of a sudden it's like, Hey Lalli is my vest plugged in? Fuck. Nope. I would just mess with them. So, that kind of humor was fun.

In Italy where I moved to after Iraq, I was especially flying with people from our company, I'd have big bolts in my pockets of my flight suit. I'd say, hey sir, well I could give you something for a bumpy ride. So he was kind of kicking at the trim and our aircraft fired a lot, and dropped the bolts out of my pocket. The passenger picked up those suckers, they were rot out. I grabbed the bolts from him, I look at it and turn them over in my hand, I shrugged my shoulders and I throw them out the window.

So, they would be petrified. You have fun. It helps break up the monotony of the flights where just when you're up in the air for five, six hours at a time, you get creative with entertainment.

Ken Harbaugh:

Did you ever carry civilian passengers that just did not have that composure in the air that you expected?

Yeah. We flew civilian customers often, especially in Europe. A lot of the press callers that we flew were a little more for lack of better words, gun-shy both in-theater and in peace-time flights. But you kind of just say, hey if you're going to get sick in the aircraft, well you're going to clean it up at the end of the flight. So, down your shirt, into your helmet, that's it. Yeah, I guess it really depended on who was doing it, and who your customers were that day.

Ken Harbaugh:

Got it. Well, let's talk about leaving Iraq. Did you head back to the States before going to Italy? And I assume you did. What was the feeling like completing a combat deployment, realizing you're still in one piece and heading home?

SSG Mark Lalli:

Well, it was a little anticlimactic. You're like, hey I just survived a year in combat. I got shot at and I shot back and I'm still in one piece, so I kind of felt a little invincible. I turned 21 when I was in combat, so I had really made up for lost time, so to speak I thought with kind of enjoying myself, and enjoying the company of others. After I got back to the States, it was about a month before I got orders to go to Europe. And then I remember I said, okay, well I'll try to study Italian. I tried to study where I was going to be at in-country. I tried to study different parts of the culture to kind of immerse myself so I could fit in and not stick out like a sore thumb. And, just learn as much as I could about a newer setting I'd be in.

Ken Harbaugh:

What was the mission in Italy? Was it mostly training?

SSG Mark Lalli:

Yeah. Our primary mission in Italy was to fly general support. Our unit's headquarters was in Mannheim, Germany. However, our battalion had a couple of companies in Mannheim, a couple of companies throughout Germany, a company in Central Europe, basically in Turkey. I was staying in Italy flying and supporting the different generals throughout Europe. Our primary job later on in Italy was to support the Southern European Task Force Commander out of Vicenza. He was a full bird colonel, and we would fly him to different meetings throughout the country just to witness different training exercises with American, Italian, and other Southern European countries.

I flew to Germany to do a mission flying support for President Bush and his White House staff. I flew missions to Romania training with the American Army, or the Romanian Army, to try to get them working together for the GWOT, Global War On Terror, and really just making sure we're all one unit working together.

Ken Harbaugh:

After combat deployment in Iraq, did Aviano feel like Disney World?

SSG Mark Lalli:

We joke about it in the Army, that whenever an airman stays at an Army installation, they get living allowances. So when we were in Italy, it was like Club Med for us. They put up Army installations in these spots on the frontier where we were fighting the Indians back in the 1800s and stuff, and then as we expanded we expanded further West. With the Air Force, they put these spaces where a senator likes to go on vacation, so they have a place just to land a plane. So, they're always these nicer kind of Club Med type bases.

But, the Italians were great people to be working with there in-country. That part of the country was a lot like American Appalachia where it was very agrarian, very fresh foods, fresh everything like that. People were always friendly to you as long as you made the effort to try to speak Italian to them and say hi at least, they would be friendly towards you. So, it was an easy situation to be in.

Ken Harbaugh:

Can you talk about the day of the accident? If you're comfortable talking about it, how it began, and just how days that end like yours did often begin perfectly normally.

SSG Mark Lalli:

Yes, sir. So on November 8th, 2007, I drove from my apartment to the base expecting to take one of my subordinate soldiers to the promotion board so he could get his interview for his sergeant. He interviewed to become a non-commissioned officer. When I got to the hangar, I was told, “Hey Lalli we changed your mission. You're going to now be flying this mission. It's going to be a show with the Air Force in an attempt to fly our front airman. Who wants to bring this on board?”

Okay. I threw my flight suit on, put on my gear, told the guy I was supposed to take the promotion board, I say, hey, good luck, do your best, have fun, and I got ready for the flight. I preflight-ed, briefed with the pilots, briefed with the crew, briefed with the passengers to prepare them and say, hey, this is what we'll be doing. Here's where we'll be going, and let's go have fun. It was the perfect day to fly, clear blue skies and it was nice. It was pretty cold that morning. It was perfect weather to fly.

I took the customers through our training areas to show them what it's like to fly in a combat situation where we're flying over air and back at the earth to everything well within the aircraft's limits, pushing the envelope but not doing anything out of the ordinary or what it's built to do. And towards the end of the flight, we came to hover to call back to base for clearance to fly home and in the valley at the time the river was pretty low, if any water in the river.

And so, the aircraft started to spin. Not really thinking it was anything unusual, I remember calling the pilot saying, “Hey sir, are we going to stop this?” When he responded with, “I can't,” I knew this wasn't going to end well.

This was a procedure that we had trained for countless times, but knew that there's really no way of recovering from this kind of malfunction.

I locked my seat belts, turned to the passengers in the back and tried to reassure them because at first they thought it was part of the show too and they were cheering, and then all of a sudden those cheers turned to screams. And, I tried to reassure them that it would be all right. Just sit up straight, keep your feet down, we'll be all right, but the aircraft hit the ground and I was knocked out upon impact.

The pilot to my left, my good friend Dave and the passenger to my right, a captain in the Air Force were both killed on impact. I was crushed in between parts of the airframe. We lost six total that day, and the other five survivors, the other four were up the walkway with minor injuries or no injuries at all. And, it all depended on where you were in the aircraft whatever severity your injuries were.

The Italian rescue crew was on scene within five minutes from our crash. There was actually a civilian Italian medevac flying around on their training machine also, not far from where we were in flight. They were on scene, and they got us cut out. They got the survivors placed up, got myself and one of the other pilots to the hospital as fast as they could. Unfortunately, Christian died not long after we arrived at the hospital and it was, yeah, that's not a good day to remember.

Ken Harbaugh:

Can you describe your condition when they cut you out of that aircraft?

SSG Mark Lalli:

I was crushed from my head to my hips. The way the aircraft broke inside, I was crushed between parts of the main transmission, the engines, and just other parts of the airframe. I fractured my skull in a couple places, both shoulder blades fractured, one shattered, several ribs fractured. I fractured seven vertebrae. My pelvis was absolutely shattered and crushed. Because of that, one leg is longer than the other leg because of the way the pelvis healed. I'd have to re-break it to get that even again. That's not something I want to do. Yeah, and so that's about it.

Ken Harbaugh:

Do you remember being cut out or is your first recollection from the hospital?

SSG Mark Lalli:

My very first memory, clear memory was after I was at rehab at James Haley VA Hospital in Tampa, Florida. That was the fourth or fifth hospital I was at after the crash. I spent about a month in Italian hospitals in a coma. I spent a week at Landstuhl Medical Center in Germany, where I kind of started to respond to commands from nurses and doctors. I was then transported to Walter Reed where I really fully regained consciousness, but I can't recall any of that time. And then after Walter Reed, I was sent to the VA in Tampa, Florida for rehab, cognitive and physical rehab, where I have my first clear memory from that time.

Ken Harbaugh:

Did they induce that coma or were you just out until you woke up?

SSG Mark Lalli:

Let's see, for the first bit of the coma, it was natural. I was knocked out, and with my traumatic brain injury I suffered bleeds inside of my brain and that helped shut the brain down. After a few weeks, I started regain consciousness on my own, but the doctors felt that I was still too unstable with my broken bones and internal injuries to really be mobile so they induced me a little bit, so for another little while, a few weeks or so.

Ken Harbaugh:

So you're rehabbing in Tampa. Did you ever go through that thought process that many of my buddies has where you're wondering if it's worth it? And I want this to be positive, so I want to get to the realization that, yeah, this is worth it. I've got a lot left to do.

SSG Mark Lalli:

I had that thought often, if not daily for a while thinking,

"Okay, well, I made it. Why am I here? Why? What's the point of me being here if I am in a chair, if I am unable to do things like I used to, live my life like I used to do?"

But, I saw a TV show where they talked about, it was on the New York Firefighters, and they talked about not having a monument for the 9/11 firefighters after the attacks. And the chief, a Vietnam vet says, “If you want to memorialize these guys, talk about them, tell stories about them, tell the other young firefighters about how brave these men were,” talking about the different guys that he served in Vietnam with and how a couple of them didn't come home. And, how it's his duty to live for those guys and their memories. I thought, that's my purpose to live that gives Christian and Dave, my pods that day, the credit for me being here.

I became obsessive by finding out what happened with our crash after really regaining consciousness, and where I looked at everything from the official Army investigations to different Italian newspaper articles. I came across the picture of the aircraft at the crash site, where we were on a sandbar that if we had hit 10 feet one way, maybe five feet the other way, we all would've drowned, nobody would've survived. I realized that I'm here, I have this chance because Christian and Dave aren't here.

So to honor them, to honor their memory, to honor their legacy, to memorialize their sacrifice, what's the best way to live? But to live and to live fully, and to really go all in and really not take all the opportunities that I could to really better myself, better my family, better my communities, and really help carry on the legacy that they couldn't carry on. And that's become my mission, become my purpose, become my drive with everything I do now.

Ken Harbaugh:

Can you share with us your best memories of Christian and Dave?

SSG Mark Lalli:

So Dave and I, we flew together a lot. I probably flew with him probably more than a lot of the other pilots in Italy. He was with me on the mission to Germany, or flying, or President Bush's staff for the GSM in 2007. We had a lot of fun times then, shared a lot of beers. He was also with me when I deployed to Romania, where my PTS from my combat tour a year prior was really starting to get to me and being a prior service crew chief actually helps, or kind of helped me.

We got to talking about things that helped heal me or helped him. It was therapeutic for me to talk about. Christian was our company commander. I saw a lot of my older brother in him. He would always try. He led, but he was never authoritarian. He was never forceful with his leadership. He was always quick with a joke, a smile, and always quick to make the Chewbacca noise. Whenever we were kind of just in a lull in the conversation, a lull in just the day, he would just be forced to make a joke, crack up things I guess with a smile and you'd just feel better. And that's, you'd expect him for that.

Ken Harbaugh:

What was your experience with the VA and with the other support organizations like the Wounded Warrior Project?

SSG Mark Lalli:

The Wounded Warrior Project, they were the first ones to really come to bat for me. When I was first in the hospital, I remember the guy came into my room with a milkshake saying, hey, I'm Jonathan. How are we doing today? Thank you, yeah, good looking. I mean, there's no turning down a free milkshake when they're serving me crap for hospital food all day. Then hearing him telling me stories about everything from some of the dolphins to offshore fishing, to riding his bike from Miami to Key West, that's pretty cool. So, he walked out. I was standing on one leg and I thought, this guy could do it with one leg, what's my excuse?

So when I got out of the hospital and I was retired from the Army, I signed up to do more events with the Wounded Warrior Project. I really felt a click there, I felt home with my tribe of other warriors and other family members, and I just felt a belonging. As far as the VA goes, I cannot say a bad thing about the VA, or about the Tampa VA. The doctors there, I felt they all had my best, best outcome in mind.

Yeah, I mean, it's like any other government organization where yeah, you can have some hiccups, you're going to have some issues here, but from my perspective if you treat people the way you want to be treated they're going to treat you well. If you walk into an appointment yelling and screaming at the lady behind the desk at the computer, she's not going to help you. She's not going to be able to do anything for you if you can't do anything other than do schedules anyway. So, it's not really worth getting your panties in a wad over them not helping you. You get out what you put in. So, I've always had a great experience with them, and I would not be here without, well I would not be to the level I am without their care and compassion, and work that they put in.

Ken Harbaugh:

You have this incredible looking flag behind you. Can you describe what I’m talking about and explain its significance?

SSG Mark Lalli:

Yeah, behind me is a framed American flag, it is. When I first got to Kuwait, I bought a flag at the BX and I had a folder with me. I'm having to fly a back, every time we flew on a mission in-country, I put it up on the dashboard of the aircraft and brought it home with me. And, it's framed in my office also. And then when I was in Italy, I did the same thing with the flag there. I put in my helmet bag, it flew with me every time we flew on a mission. And, the flag behind me was with me when we crashed. The white stripes are now yellow stripes. The white stars are now yellow stars and it had been stained from hydraulic fluid, jet fuel, and other parts of the aircraft fluid, and maybe even some bodily fluids from some of those not so lucky. When my company came to the crash site after the initial impact, one of my subordinate soldiers ran to where my seat was. I had since been evacuated from the aircraft, and I was in the hospital. He went to where my helmet bag was, grabbed the flag from the bag, and he kept it or gave it to my dad and said, hey, this is for Mark. He needs to have this. So when I got out of rehab, my dad gave it to me and said, “Jackson gave this to me. He said you'll want this.” “What do you mean? You better believe I want that.” So, that's the history behind that flag.

Ken Harbaugh:

Well, thank you so much, Mark, for sharing with us. Really appreciate it. Is there anything else you want to add for our listeners?

SSG Mark Lalli:

Just that there's a lot that I could say, but it's all cliched stuff that just be, just to help us carry on our legacies and the legacies of our brothers and sisters who didn't come home.

Ken Harbaugh:

Thanks, Mark.

Thank you for reading this Warriors In Their Own Words web-exclusive interview with SSG Mark Lalli.

Next week on April 15th, SSG Lalli will be racing in the Boston Marathon with the help of his hand cycle. He’s raising money for the National Braille Press, a non-profit that provides programs and materials to the visually impaired, like his daughter. You can help Lalli reach his goal by donating here.

If you or a loved one is interested in sharing your story of service to our country, reach out to our team at [email protected]. You can have your story archived in the Library of Congress, and possibly be featured on our show!